Toyota BJ40 Land Cruiser

Howard Threadgill was a civil engineer. He spent a significant part of his career in the Middle East, in countries like Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Libya and Qatar. The work often involved travelling into the less developed parts of the countries. The company vehicles he generally used were Toyota Land Cruisers. They were in his words “totally reliable, durable and virtually bulletproof” in all sorts of challenging conditions.

On his return to the UK, he started a small collection of Land Cruisers. The challenge was to find a 40 series model of the type he first used that was in original condition. Utilitarian vehicles, by their very nature, tend to be hard used, with modifications undertaken from a practical usage perspective.

Unable to find a machine that met his requirements, he started to look across Europe. The nearest to stock model he could locate, after a long search, was found in Madeira, the autonomous region of Portugal. It was owned by a Mini Moke restorer!

A deal was struck and the J40 was shipped to England and has pride of place in Howard’s collection. He says they are easy to work on and spares are available from Japan, Australia, Holland, Portugal and the UK.

Howard’s aim is to keep it in original condition, not ‘concours’ but as close to leaving the factory as possible. The paint is original and while his more modern daily driver Land Cruiser is left outside the J40 is kept securely in a garage. Every time he drives it, the Land Cruiser brings a smile to his face, he says “it’s like travelling with a reliable friend” which has many great memories.

pics K Gibbins

A PDF can be downloaded here

Talbot Introduction

This article epitomises the enthusiasm required to undertake the purchase and preservation of a historic vehicle. As the owner says, “I feel I am doing my part, however small, to keep a unique piece of motoring heritage alive” and part of the reward is “…, it has provided a huge amount of enjoyment, both for me and hopefully for others, too – whether they be laughing at the ridiculousness of it or admiring its survival.”

For the background to Talbot cars, an excellent video, History of Talbot Cars 1903-2003, produced by the Sunbeam Talbot Darracq Register[1] can be seen on YouTube[2]

[1] Sunbeam Talbot Darracq Register - The Sunbeam Talbot Darracq Register (stdregister.org)

[2] https://youtu.be/G6B9JVO8h8w

TALES OF A TALBOT

(Article courtesy of The Automobile magazine)

Young enthusiast Toby Bruce wasn’t looking for a Vintage saloon, but once he found this forlorn 1926 Talbot DC he knew he had to have it. Photographs by Stefan Marjoram

|

|

“What’s a young chap like you doing with a car like this?” That kind of question is a common occurrence when people see me with my Talbot. Yes, perhaps it is a strange choice for a young person in this day and age, when tastes in every area – not just in cars – are rapidly changing, and the amazing leaps in technology have made much of the last century’s innovations obsolete. Perhaps it would have made sense for my car-mad brain to be drawn more towards those cars that were significant when I was at my most impressionable stage – things such as the Nissan Skyline GTR, the Toyota Supra, the Mazda MX-5, and other such ‘icons’ of the 1990s.

But that not what happened. Put it down to what you will. A desire to be different? A somewhat contrary nature? That I can’t answer, and I have often wondered myself. Really, I think it comes down to taste – some people, just by the ways their brains work, are more likely to be drawn to different things, and that sometimes defies any logical explanation. As I’ve got older, I have also started to feel a strong desire to preserve elements of our motoring heritage that otherwise are at risk because of the apathy of many younger people towards prewar cars and the voracious appetite of unscrupulous special-builders for prewar saloons.

It is perhaps this latter fact that led me to acquire this 1926 Talbot 10cv DC. When I saw it for the first time, it struck me it would probably be more valuable as a rolling chassis, ready for a pointy-tailed sporty body, than as a complete car. I instantly felt rather protective of it, even though it wasn’t mine – the thought of such an original artefact being lost forever was rather disturbing.

It’s what I call a ‘non-sports saloon’ – unlike many saloons from the following decade, there’s no attempt whatsoever to make any concessions to sporting style. The body, made in the Talbot factory at Suresnes to Weymann patents, is as upright as a block of flats, and about as aerodynamic as one. It is, I concede, a rather unfashionable style in today’s old-car market.

The condition of the car would perhaps indicate a long and storied life with many tales to tell; maybe it would tell those tales if it could. Unfortunately, though it is a surprisingly capable vehicle in many ways, it is still not capable of speech, so those tales shall remain untold. What little I do know about the car I learnt from the auction catalogue. It was dug out of storage in France in the late 1990s and put back on the road. Imported to the UK in 2000, it spent most of its time thereafter in storage as part of the collection of the late Peter Helder. It shared its garage with several other products of the Suresnes factory – a 20/98 TL Weymann saloon, a Type A V8, and a unique DTS, the last survivor of that model.

After Peter died, his cars were sold by Richard Edmonds Auctions in Wiltshire. That was where I first saw the Talbot. Despite my first reaction being one of protectiveness and admiration, it was not an easy decision to try to acquire it. I felt at the time, and still do to a certain extent, that it could be a recipe for heartbreak – keeping a car in such a state cannot last forever. But we shall have to cross that bridge when we come to it, and I hope it is a long way off. The reason I took the plunge is that I have an extremely strong empathy for Oily Rag vehicles, or ‘oily rag’ anything, for that matter. In my view, an old object should look old.

Thinking about it the night before the auction, I decided there are few cars as Oily Rag but simultaneously structurally sound as this one, and that it was probably a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity I would always regret if I missed it. As I could not bid myself, I engaged the help of my father to raise a hand on my behalf. Come the end of the auction, we were in luck and the Talbot was making the short trip home.

Delivered on a trailer, it was parked up in the empty barn in the farmyard next door. Inspecting it as its owner for the first time, I removed a box of what I thought were old rags from the back seat. On closer inspection, these turned out to be the original seat and door covers, still in superb condition. After being carefully cleaned and fitted, they really added an extra layer of charm to the car – an unexpected bonus. Meanwhile, other details came to light – the fine cut-glass oil sidelamps, which I’m told had to be lit while driving in French towns in the ’20s; the complicated mechanical dipping system for the headlamps, with five different positions; the stickers adorning the front and rear screens promoting the Club des Sans-Clubs – I never have discovered what this was. One of the stickers on the inside of the rear window is particularly interesting: roughly translated from the French, it tells the driver not to let the actions and chit-chat of passengers distract him or her from the road. The fact the driver could only read this by turning round and not looking at the road at all is rather ironic.

Now more familiar with the car, we considered the next steps. At this point I didn’t actually know very much about the model – to me, the details were secondary to the condition. With the help of a fellow DC owner and the internet, I found out much more about it very quickly, though. The DC model was introduced in 1923 as part of a rather large Talbot-Darracq range – somewhat confusingly, they were sold as Darracqs in the UK, and as Talbot-Darracqs (by 1926 just Talbot) in France. In French, of course, it’s pronounced without the ‘t’ at the end – though I always feel rather pretentious when doing that. Notable features of the model were excellent four-wheel brakes and a new overhead-valve 1.6-litre engine – a very smooth unit, driving through a three-speed gearbox. These all rode on an extremely strong chassis, and the resulting car was a high-quality offering in its market segment. From pictures I have seen online, a huge variety of bodies was fitted to the DC chassis, from sporting two-seaters to landaulets. I’m not sure I have ever seen two the same.

Armed with this new information, the recommissioning process began. An oil change was, of course, first on the list. A very worthwhile exercise it was, too – what came out can most accurately be described as treacle-like. Having flushed the engine several times, it finally got all the nasty goo out of the system and it was on to the next thing – a new battery. Not quite as taxing, that one. More in hope than expectation, we put some fuel in the tank and filled up the Weymann Exhausteur – the French equivalent of an Autovac.

Then followed a wild goose chase round the various unmarked switches on the dash, trying to figure out which one was the ignition. Eventually we found it, but the spark was rather weak. We ‘borrowed’ the spare coil from my Morris Traveller, hung it on the spare spark plug holder (where it would remain for the next two years) and, to my great surprise, the engine sprang into life. Sitting in the driver’s seat, I selected first gear, let the clutch in, and went backwards. In my excitement I’d forgotten it was a three-speed…

Having selected a forward gear, I eased the Talbot out of the barn and did a lap of the field. This went so well, I decided to be brave and ventured out into the village; sure enough, about two minutes later I was stranded on the village green. The petrol tap had vibrated itself shut – it really needs to be made extremely tight. Since then, however, the engine has always started first time.

The first proper trip out for the Talbot was to the Post Office in the nearest town, three miles away. I made the mistake of doing this when the children were leaving school. As I was parked up on the high street, a boy of about 12 shouted out “Your car’s broken, mate!”, much to the joy of his easily-amused chums. ‘How rude,’ I thought, and almost immediately collapsed backwards, as the leather strap that holds the back of the front seat up gave way. Very much hoping this had gone unseen by the budding young comedian, I made my way home, hanging on to the steering wheel so as not to become an inadvertent back-seat driver. I must admit the seat wasn’t properly fixed until the day before these photographs were taken – until that point I had used a cut-down wooden post to prop it up…

The first real long-distance drive (everything is relative) was to VSCC Prescott in August, 2017. Much to my surprise, I made it there in one piece, even touching an indicated 60mph on a slightly – well, more than slightly – downhill section of the Fosse Way. The car seemed to garner plenty of positive comments from fellow attendees, and this came as something of a relief. The journey back, however, was not quite as successful.

I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say it could have been the last journey for both me and the car. On the road between Cirencester and Malmesbury, I was tailgated mercilessly by an articulated lorry – he can’t have been more than 10ft behind for the best part of 10 miles. I wasn’t hanging around – in fact, I was pushing it as hard as felt sensible – but also couldn’t stop to let him past, as I was worried any sudden braking would see him running straight into the back of me. Then, just north of Malmesbury, the left rear tyre came off the rim. In my naivety, I had been running the tyres at the pressures they were when I got it – that is, about 35psi. I didn’t realise they were beaded-edge, and hence should be at about 65psi. This was, of course, the root cause of tyre and rim parting company.

Somehow, the lorry swerved round me and zoomed off into the distance. The next person who came along – in a modern Volvo – slowed down to look at the poor stranded Talbot, but as soon as they saw that I might appreciate some assistance, they looked away and drove off – an all-too-common occurrence, I find, in today’s world. Now, I had neglected to bring a jack with me for this trip, so I had to make a sheepish phone call to my father, who had just got back from Prescott in his 1931 Two Litre supercharged Lagonda. He duly set out with a jack to rescue me, and we were going again before dusk. I counted that as a lucky escape. Needless to say, once I had got on the internet and figured out that I was running the tyres at far too low a pressure, they were duly inflated further.

That was not the end of the tyre woes, though. Attending Beaulieu Autojumble the following month, I thought I should look around for any tyres of the correct size, as I had not found any on the internet. A visit to one of the tyre experts there produced surprised noises on their part, as they informed me that no tyres at all had been made in that size for 20 years or more, so I’d better look after the ones I’d got. This is easier said than done, as would be shown again in 2018.

The Talbot’s last engagement of 2017 was in September, when I used it to attend my first school reunion. Now, the fact I was going to a school reunion did, in itself, make me feel somewhat old. By the end of that night I felt positively ancient, having ‘slept’ for five hours on the back seat of the Talbot, in a pub car park, with three of the four windows stuck down. This, I feel, does speed up the ageing process, though I am not going to volunteer to do it again to prove the scientific validity of that statement.

Anyway, the Talbot had made it there, no problem. It was going very well, in fact. It even managed not to break while giving a few of my former classmates a lift down the road to the pub. However, it was reluctant to leave said pub. At around midnight I was about to set off, pressed the starter button, and… nothing. Don’t worry, I thought, it’s just decided not to work. I’ll bump-start it. That attempt brought the car to an instant halt – obviously something was not right.

As it was dark and cold, I thought it better just to call the AA rather than try and fail to do anything competent. After a protracted session of begging over the phone – something I have become an expert at, though I’m not proud of the fact – they agreed to send a recovery lorry instead of a van. Although it is their policy to send a van first, even if you know they won’t be able to fix it, sometimes if you adopt an extra-pitiful tone this step can be skipped – something worth keeping in mind for fellow AA members out there. However, as Friday night tends to be a busy one for the breakdown services, there was quite a wait – five hours, to be precise. The last stragglers from the reunion dispersed, and I was left alone – or so I thought.

As I settled down on the back seat to wait, I heard a noise I hadn’t heard for a while. It sounded like a rugby scrum. Sure enough, as I peered out of the window, I spotted three former members of the school rugby team, who had evidently decided see whether they could lift the poor Skoda that was meant to be their transport home on to two wheels. Hoping they wouldn’t turn their attentions to the Talbot instead, I sank down again into the rather spacious back seat, covered myself with a blanket and waited. When the lorry finally turned up at 5am, the driver must have got quite a shock – a car that looked as if it had stepped straight out of the 1920s, with me half-asleep on the back seat, still dressed to the nines in a dinner jacket and intentionally tasteless Cambridge University Tiddlywinks Club bow tie…

Following this escapade, I went off to live and study in Sweden, and the Talbot was put away and remained untouched until the following summer. The problem, it turned out, was rather simple – the starter had got stuck on the ring. My fears of a seized engine were unfounded. With old cars, my default assumption is always that it’s as bad as it can be. The starter was very difficult to extract, but once out it was easily sorted, and the car was fully operational for its first trip of 2018 – to Prescott again, this time for the Vintage Minor Register’s superb Prewar Prescott event.

Again, it went extremely well on the way there. Well, almost all of the way there. Over the last few miles, I noticed a progressive reduction in power – so much so that, by the time I attempted my first run up the famous hill, the poor car was struggling even to make it off the start line. Of course, this was not a timed event, but my father recorded that run from the passenger seat. Watching the video that evening, I timed it at 2min 40sec – surely one of the slowest times ever set at Prescott by someone who was driving pretty much flat-out.

From behind the car, listening to the exhaust – not inside or in the engine bay, though – I could hear it was missing and something was clearly amiss. However, with good oil pressure and no signs of boiling, I decided to try to get home unaided. In this I succeeded, to everyone’s surprise, despite getting hopelessly lost in Cheltenham – the original owner of this particular Talbot DC did not specify a GPS system, unfortunately.

The next day, the head came off and the cause of my woes was immediately clear – a valve burnt almost beyond recognition. My ever-helpful father took a trip to a place in the east – Sussex, I think – and returned triumphantly with eight brand new valves. These were installed and by the following weekend, everything was ready for an extremely daft expedition – a round trip of more than 300 miles.

This occasion was the VSCC Summer Rally, based that year at Goodwood, where the club was also running a sprint. Goodwood is 100 miles from home, if one keeps off the motorway. I figured this would take around three hours, and then I figured that I’m normally very wrong on the timing front so I left home in the dark and drizzle at 4.30am. This gave me ample opportunity to appreciate one of my favourite features of the Talbot, and indeed of any old French car – the wonderful warm glow emitted by the ‘selective yellow’ headlamps.

Unfortunately, this was an opportunity I did not maximise, as I was too busy concentrating on various issues – the recalcitrant vacuum-operated wiper, the occasional drops of water that seemed to come from nowhere and hit me in the face and, most importantly, the fact I had forgotten to bring any breakfast with me.

Mercifully, dawn soon broke and the driving became much more enjoyable. In fact, I was making excellent progress. This optimistic thought was just running through my mind on the dual carriageway north of Winchester, flying along – relatively speaking – at 50mph. The perils of positive thought: in an instant, I got that now-familiar swaying from the rear axle and the chorus of horns from the cars passing me – yes, one of the rear tyres had given up again, this time the nearside rear. I pulled over on to the verge, but still, it was somewhat precarious – annoyingly, I’d driven past a large layby just half a mile or so before. But never mind, it was sure to be only a short breakdown as, of course, I had remembered to bring a jack with me this time, hadn’t I?

I hadn’t. By this time it was 7am, and that seemed a good time to need the AA, as there was a van there in a flash. Around the same time as the AA patrol arrived, my father, who had bravely volunteered to be my navigator for this undertaking, arrived in his modern car, with such luxuries as fully-inflated tyres. With the wheel swapped for the better of the two spares, we set off again. The modern thing was left by the roadside as soon as possible and my father joined me for the rest of the drive.

On arrival at Goodwood, a scrutineer was found – we were a bit late, but just about made it – and I signed on and got the route for the day. Well, I might as well not have bothered with the route. On that particular day, right became left and left became backwards, round the roundabout, no, not that roundabout… Two tired minds do not make a great navigational team, but we had fun, made it to most checkpoints through luck more than judgment, and finished last. But at least we finished – I’m always satisfied with that.

The homeward trip was uneventful. After picking up the modern, my father followed me for a while on the dual carriageway. With his GPS on, he reported that the Talbot was cruising at a steady 53mph – not at all bad, I thought. I’ve always reckoned that a good useable Vintage car should be capable of cruising at around 50. Unfortunately, it seems many of the smaller-capacity French cars of the era are not capable of that, so in my view that ability is a fine endorsement of the high-quality output of the Suresnes factory. Indeed, in contemporary reviews, the DC model was highly praised for its remarkably fast cross-country progress for a car of its class.

Since the burnt valve issue, the Talbot has performed reliably, even making it both to and from Prewar Prescott without any issues – I consider that curse lifted now. However, in the latter part of 2019, it developed a worrying habit of spewing a prodigious fountain of petrol from the top of its carburetter. As this was a non-original Cozette – presumably fitted during the recommissioning in around 2000 – I decided to look into replacing it with something better. The Cozette enabled the car to move, but it really wasn’t ideal – every time I went round a left-hand bend it would play up, and sometimes the car would just stop for seemingly no reason. Anyway, I reasoned, I’d rather own an Oily Rag car than an Oily Rag bonfire.

For ease of tuning and parts availability, a period SU seemed like the best option, so one of suitable size was acquired at Beaulieu Autojumble in 2019. Over the winter, the inlet manifold was very slightly modified to accept this, and this summer I finally got to drive it. To my surprise, it started first time, as it always did and still does. After the first lockdown, in convoy with my father in his MG M-Type, we drove down to a rolling road in Dorset to set up the carburetter properly – it was running very rich as it was, but that was soon rectified. Although we didn’t submit the poor thing to a full power run, I did read 21bhp at the wheels on the screen – not at all bad, considering that from the factory it was rated at 32 at the flywheel.

The M-Type also had its time on the rollers and we set off back to Wiltshire, I with my terrible sense of direction following. Those of an octagonal persuasion may not want to read this part: the Talbot turned out to be quite a bit quicker, both when climbing steep hills and cruising on the flat. Until it was brought out for the photographs to be taken for this article, that was the last time the Talbot had been out on the road. I had several events planned for it, but of course almost everything fell by the wayside in 2020. This year, as I’m sure we all hope, much more old-car-based fun will be possible.

Thinking back now to when I first got the car, two things spring to mind. First, I’m surprised it hasn’t deteriorated to any notable degree, despite my inexperience in dealing with such a fragile vehicle. Secondly, I am extremely glad it came into my possession, for several reasons. Most importantly, it has provided a huge amount of enjoyment, both for me and hopefully for others, too – whether they be laughing at the ridiculousness of it, or admiring its survival. In addition, I feel I am doing my part, however small, to keep a unique piece of motoring heritage alive. As I’m sure many readers were when it was reported in the November issue, I was infuriated by the recent destruction by a European dealer of that wonderful Amilcar M-Type saloon. I felt the loss particularly keenly – that car reminded me so much of this one. The more instances of destruction that occur, the more my desire grows to preserve my Talbot. At this point, I shall never part with it, though other cars may come and go. I’m sure it’ll need much work to preserve it and keep it running, but to be the custodian of a time-capsule vehicle is a joy that I don’t think can be repeated.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Photographs by Stefan Marjoram

1914 Wanderer Heeresmodell

|

|

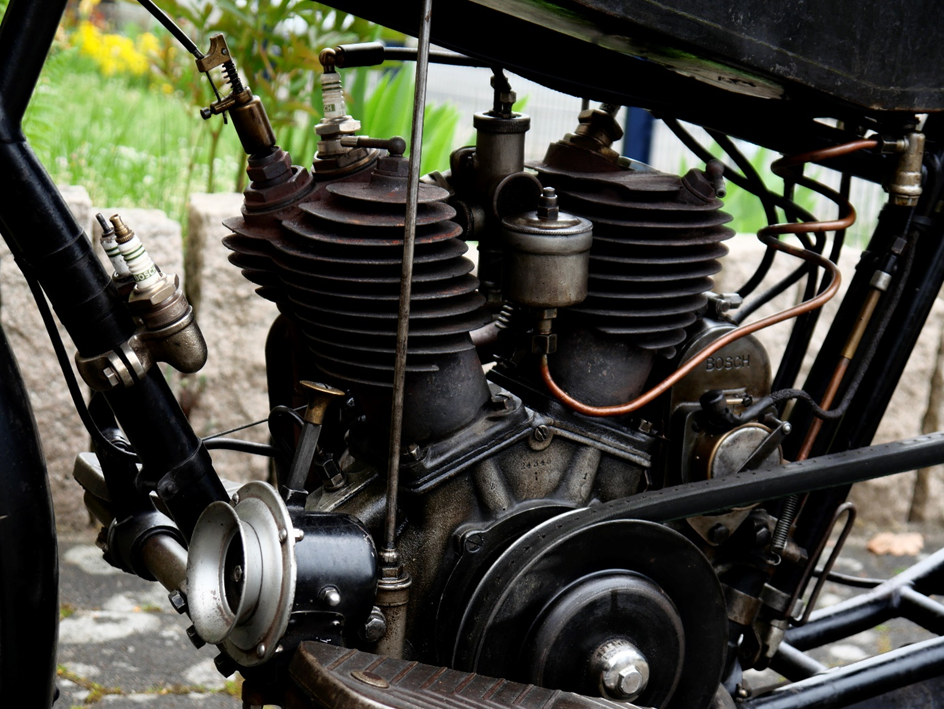

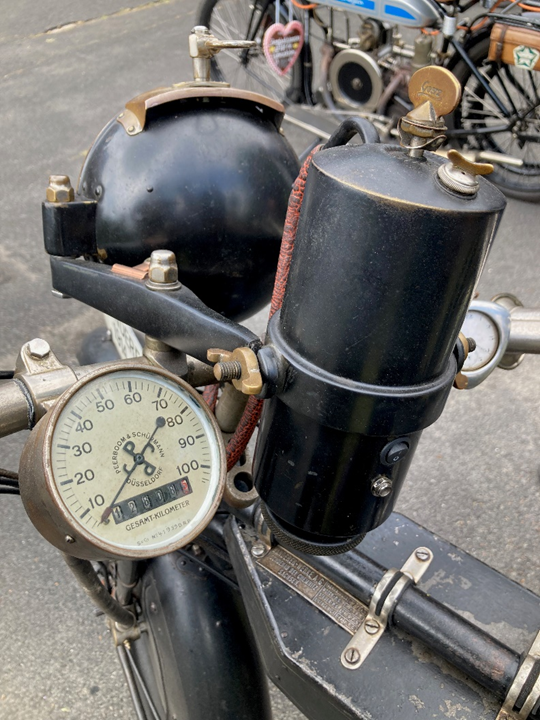

The current custodian Dieter Springer explains his rare motorcycle in his own words:

“This Wanderer "Heeresmodell", built in 1914, was owned by the family of a motorcycle dealer in Bielefeld. It had been shown at various exhibitions over the years and was well-known in the motorcycle scene. Nobody expected that this machine would ever be for sale.

By chance, however, I got this chance and was able to buy it in 2008 for a fair price.

The bike was in absolutely original condition and could be road-registered without any problems after an engine overhaul.

As I wanted to use the bike in rallies, some modifications were made to improve its operational safety.

The clutch, originally operated via a lever on the upper frame tube, was moved to the handlebars. The old clutch lever is now used to operate the exhaust flap.

The carbide lighting has been upgraded to LED lamps, which are powered by a battery.

In order to be able to restore the unique original condition of the machine at any time, the modifications, which change the appearance only very little, are completely reversible.

Since then, the Wanderer has been used at several classic car rallies every year and, apart from minor breakdowns, runs very reliably”

|

|

|

|

The reward for all this effort was the FIVA Best Preservation Award at the 2018 Ibbenbürener Motorrad-Veteranen-Rallye. PDF download here.